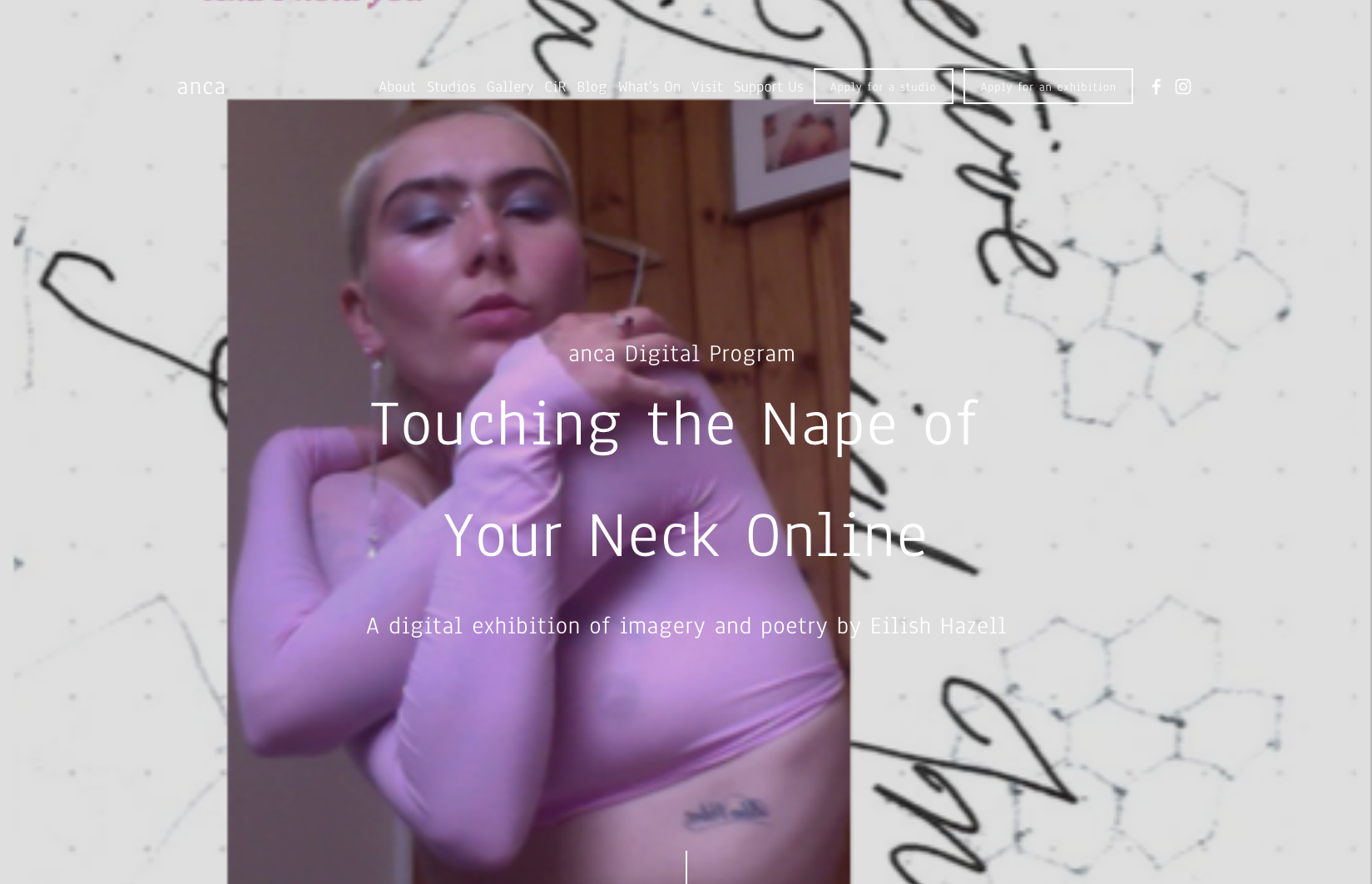

On 3 June 2020 Eilish Hazell, a queer Australian artist working in the field of performance opened their premier digital exhibition ‘Touching the Nape of Your Neck Online’ with ANCA Gallery. The show centred around four new performance works produced by and featuring the artist as they engage in exhaustive and continuous, macabre and masochistic processes to generate what Hazell refers to as ‘love letters’: intensely personal etchings of grief and loss that, through their display, function as acts of redemption by way of honesty and vulnerability. Framed by the devastating on-going crisis of COVID-19, on 17 June ANCA Gallery spoke with Hazell about their practice, digital safe spaces for queer performers and intimacy in a time of separation.

Touching the Nape of Your Neck Online is a very personal and intimate show, what was the motivations behind it?

Eilish Hazell: Apocalypse Love. Initially, I had proposed the show with the intention to continue a then ongoing collaboration with my partner at the time. My practice had recently emphasised the role of the ‘lover as collaborator’ and I wanted to explore how the intimacy between creative partnerships could be used to transform digital spaces into intimate, safe spaces. Responding to the lockdown, my intention was to foster connection and strength with others through a series of digital performances that communicated mutual care, openness and intimacy. Painfully ironically as the lockdown went on tensions affected my relationship and we ultimately broke up.

Going through a breakup in the middle of quarantine and responding to this further isolation naturally morphed my project and reinforced my need to foster community around me. It became a project of (literally) holding on to the self and holding space for the self as a means of healing and transformation as well as a means of holding space and care for others. And so for you, here are my “open love letters”- take what you will, but leave me something too.

Has self-tattooing always been a part of your practice?

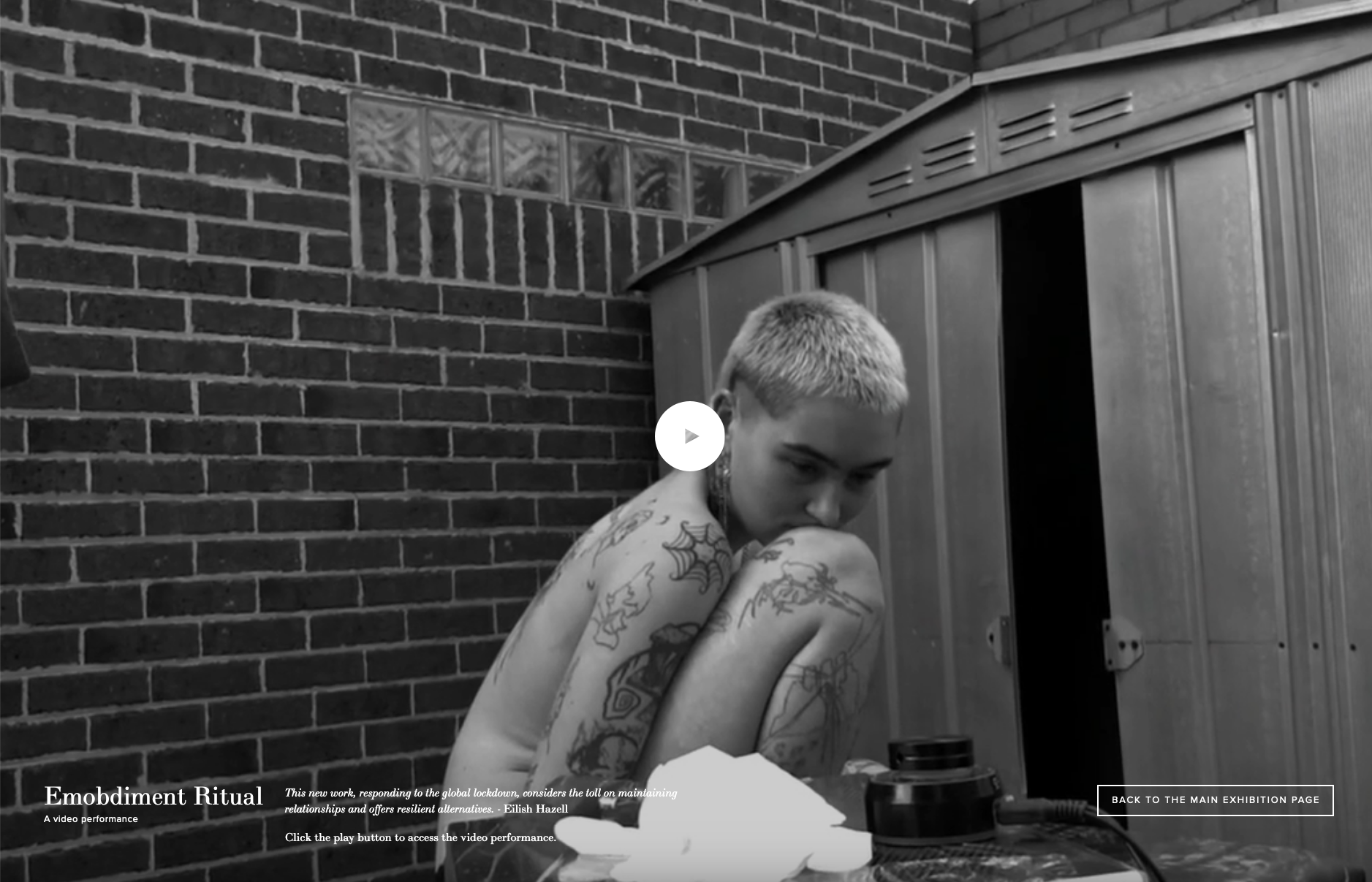

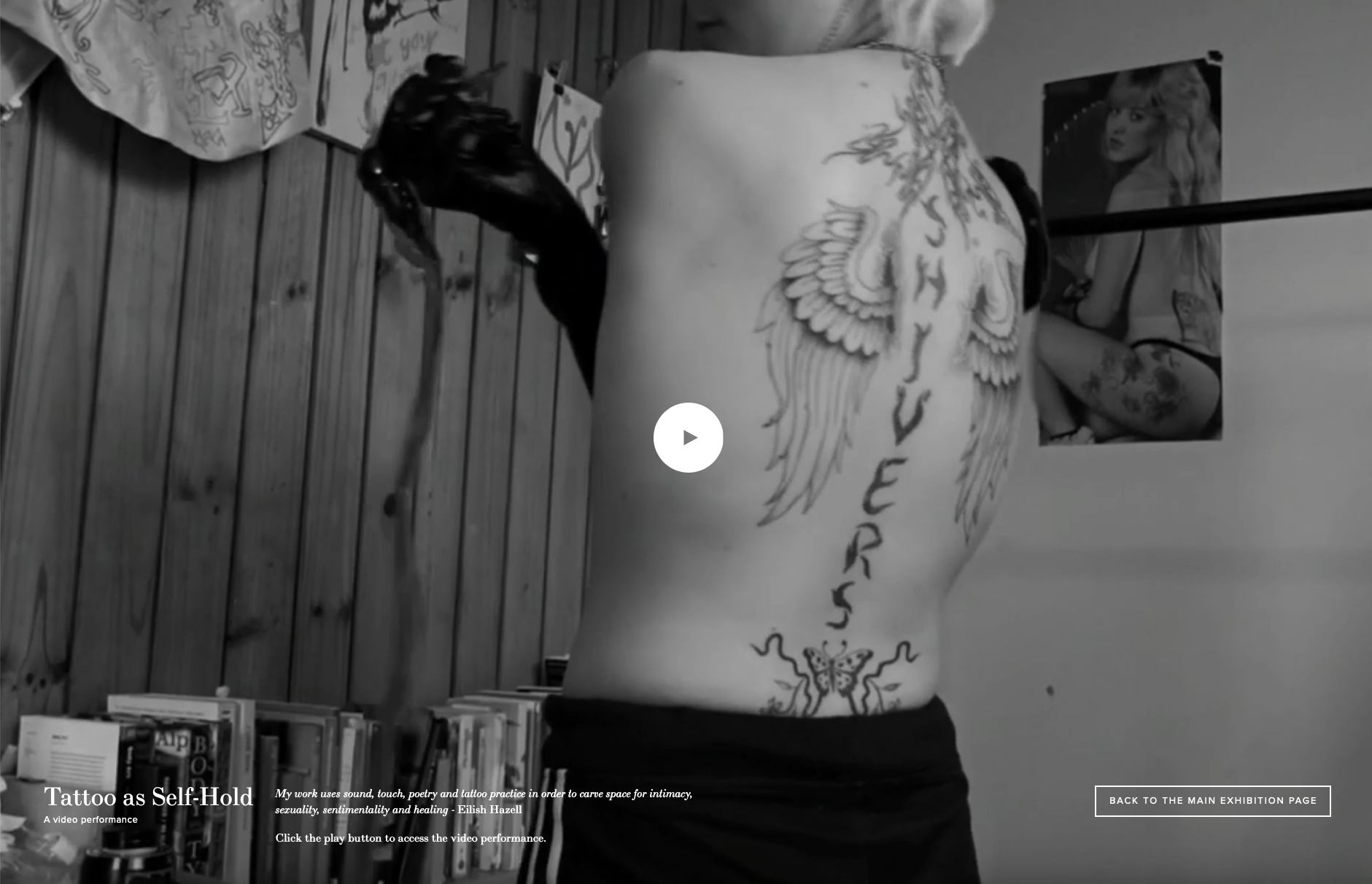

Eilish Hazell: I have been doing handpoke tattoos for about four or five years and started doing them when I was at art school studying painting but I wouldn’t say that I have always considered it part of my practice. It was something I used as a means of overcoming personally issues with self-harm and something I did drunkenly on my friends as a love language. So while I was teaching myself to tattoo by practicing on my own legs and then my friends, lovers, siblings and then strangers for money, I saw my creative practice as something separate. Last year, returning to uni for honours I realised I no longer have the patience for painting and that my real interest was always in the performative and in tattooing as creative practice.

I think my hesitation with focusing on tattooing in earlier years has had a lot to do with being self taught and having imposter syndrome in the tattoo world as well as art institutional gatekeeping and protocols that have restricted my ability to use tattooing as a medium in a gallery or university context. Earlier in January I was part of a groups show for Midsumma Festival called ‘Venus in Thorns’ in which the curator Jake Treacy worked really hard to make sure I was allowed to perform an intimate tattoo ritual within my installation in the gallery. Tattooing the self has always been an important part of how I express my queer identity, communicate desire and achieve catharsis but I think in the last two years I have realised how much importance it holds for me and how much potential the medium has in performance art once we transcend institutional hoops for it to have an audience!

In the past couple of years you have had 2 Instagram accounts disabled after posting images of your work. In your experience, what are the challenges that come with being a queer artist making work about intimacy in digital spaces?

Eilish Hazell: Earlier this week even, I had a post of a performance work from January deleted because of my dreaded, rogue ‘female’ nipple which I thought I had convincingly buried on slide three of a post. This censorship, which I am all too familiar with, has erased the record of a work that I am proud of and wish to communicate to my following. It’s continually frustrating because I do not wish to self-censor to pander to Instagram’s frankly medieval “community guidelines” but if I don’t play the game to an extent my accounts get deleted and my work loses an audience. I lose access to the ability to represent my work and I lose connection with community.

As a queer non-binary person, I have worked really hard to reclaim my body from patriarchal notions of gender and am at a point where I feel liberated and empowered representing my nakedness. So it is disheartening the way digital platforms seek to erase this representation, weaponise my body against me and reinforce the male gaze. It feels embarrassing and trivial that in 2020 we are still trying to “free the nip” but of course it is deeper than that. Digital platforms such as Instagram function as a means of silencing minorities and upholding white, cis-heteronormative capitalist patriarchy that exploit the body as commodity. Social media often functions as an extension of the police state that we live in.

Instagram’s double standard for the “female nipple” only serves to further sexualise and objectify non-male bodies and limit these people their agency. I feel as though representing self-nudity online has sometimes complicated my relationship dynamics while evoking unsolicited sexual attention. A cis-male ex partner of mine struggled with my online presence despite posting images of himself topless online as well and also struggled to recognise how he reinforced this double standard. I think representation is extremely important and I think being vulnerable and embodied in your identity on the internet inspires and empowers others to do the same. I will continue to push back against this censorship because I think my story deserves to be heard and we are stronger together. As evidenced in the current Black Lives Matter protests in America and around the world, when we are united in our activism and online awareness, we can create change.

How has COVID-19 shaped your digital exhibition Touching the Nape of Your Neck Online and how is it impacting your creative processes and outputs?

Eilish Hazell: My work has always been concerned with intimacy and connection but I think COVID-19 has definitely stirred up conversations and anxieties for me around maintaining relationships and creating communities of care despite physical barriers.

What do you want people to take away from seeing your exhibition?

Eilish Hazell: I want people to find strength and feel held!

How do you see your practice progressing into the future?

Eilish Hazell: I would like to continue to push the limits of tattooing through live performance. I believe in the transformative and meditative power of tattooing and I think its worth exploring through performance and collaboration. I think it would be cool to do a residency where I focus on endurance and conscious self-tattooing as well as collaborative works with other artists acting on each others bodies. I think a tattoo life drawing class would be an exciting examination of both the immediacy and permanence of tattooing and an interesting conversation about where tattoo sits in relation to Western art history. I think classist notions of value have limited tattooist access to fine art status and I want to push for tattooing to have a place in these contexts. But more importantly I want to break the rules and queer tattoo practice as a means of creating safe spaces outside these male-dominated traditions. As a tattoo artist I want to create a private studio that is welcoming of all bodies and work to facilitate others feeling empowered and safe in their bodies!

See below for exhibition documentation.

Title image: Eilish Hazell, Tattoo as a Self-Hold, 2020, Video Performance. Courtesy the artist.